Cleopatra and Antony

Not surprisingly, the ‘Donations of Alexandria’ caused outrage in Rome, where the rumour began to spread that Antony intended to transfer the empire’s capital from Rome to Alexandria. In 32 BC, Octavian had the Senate deprive Antony of his powers and declare war against Cleopatra, calling her a whore and a drunken Oriental. To avoid another civil war, Antony was not mentioned in the declaration, but this was to no avail and Antony decided to join the war on Cleopatra’s side.

The Battle of Actium and the Invasion of Egypt

The culmination of the war came at the naval Battle of Actium, which took place near the town of Preveza in northwestern Greece, on September 2, 31 BC. Here Mark Antony and Cleopatra’s combined force of 230 vessels and 50,000 sailors were defeated by Octavian’s navy commanded by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, effectively handing control of the Roman world over to Octavian.

In 30 BC Octavian invaded Egypt and laid siege to Alexandria. Hopelessly outnumbered, Anthony’s forces surrendered and, in the honourable Roman tradition, Antony committed suicide by falling on his sword.

The Death of Cleopatra

After Antony’s death Cleopatra’s was taken to Octavian who informed her that she would be brought to Rome and paraded in the streets as part of his Triumph. Perhaps unable to bear the thought of this humiliation, on August 12, 30 BC Cleopatra dressed in her royal robes and lay upon a golden couch with a diadem on her brow. According to tradition (found in ancient historian Plutarch, for example) she had an asp (an Egyptian cobra), brought to her concealed in a basket of figs, and died from the bite. Two of her female servants also died with her. The asp was a symbol of divine royalty to the Egyptians, so by allowing the asp to bite her, Cleopatra became immortal.

Other historians (including Joyce Tyldesley) believe that Cleopatra used either a poisonous ointment or a vial of poison to commit suicide. Cleopatra had lived thirty nine years, for twenty-two of which she had reigned as queen, and for fourteen she had been Antony’s partner in his empire. After her death her son Caesarion was declared pharaoh, but he was soon executed on Octavian’s orders. Her other children were sent to Rome to be raised by Antony’s wife, Octavia.

Statue of Cleopatra as Egyptian goddess

Cleopatra represented the last significant threat to Roman authority and her death also marks the end of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. The vast treasures of Egypt were plundered by Octavian, and Egypt itself became a new Roman province. Within a few years the Senate named Octavian Augustus and he became the first Roman Emperor, consolidating the western and eastern halves of the Republic into a Roman Empire.

Octavian later published his biography in which he stripped Cleopatra of her political ability and portrayed her as an immoral foreigner, a temptress of upright Roman men. A number of Roman historians and writers (the poets Horace and Lucan for example) reinforced the image of Cleopatra Empire an incestuous, adulterous whore who used sex to try and emasculate the Roman Empire. Unfortunately, such Roman propaganda has had a profound influence on the image of Cleopatra that has been passed down into Western culture.

The real Cleopatra was highly skilled politically (though ruthless with her enemies), popular with her subjects, spoke seven languages, and was said to be the only Ptolemy to read and speak Egyptian.

It is also a sobering thought to remember how different the history of western civilization might have been if Cleopatra had managed to create an eastern empire to rival the increasing might of Rome, which she very nearly succeeded in doing.

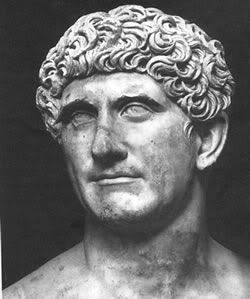

Recent archaeological work has cast some interesting but controversial light on the possible location of Cleopatra’s tomb. Greco–Roman historian Plutarch wrote that that Antony and Cleopatra were buried together, and, in 2008 archaeologists from the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities and from the Dominican Republic, working at the Temple of Taposiris Magna, 28 miles west of Alexandria, reported that one of the chambers in the building probably contained the bodies of Cleopatra and Mark Antony. The team have so far discovered 22 bronze coins inscribed with Cleopatra’s name and bearing her image, a bust of Cleopatra, and an alabaster mask believed to represent Mark Antony. Work at the site is ongoing, and only time will tell if the archaeologist are correct in their theory that the great couple were interred at such a distance from Alexandria.

Further Reading

Bradford, Ernle Cleopatra, Penguin Group New York, NY, U.S.A, 2001.

Walker, Susan; Higgs, Peter (2001), Cleopatra of Egypt, From History to Myth, Princeton University Press Ewing, New Jersey

Tyldesley Joyce, Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt. Basic Books, New York. 2008.

.

Read more about Cleopatra, Egypt’s last pharaoh,

in my book History’s Mysteries

Pages: 1 2